What are the common subjects we recognize learning in school? What do we think about for early grades (k-2)? Facts. Reading, writing, and arithmetic, right? Next will be the facts of subjects like history, geography, or science in the next level of learning (3-5). Dates. Definitions. Memorized locations. Computers is relegated to a “special” throughout. Concepts are considered higher level learning skills starting in middle school.

What are the common subjects we recognize learning in school? What do we think about for early grades (k-2)? Facts. Reading, writing, and arithmetic, right? Next will be the facts of subjects like history, geography, or science in the next level of learning (3-5). Dates. Definitions. Memorized locations. Computers is relegated to a “special” throughout. Concepts are considered higher level learning skills starting in middle school.

A well-known education philosophy called classical education, popularized in the homeschooling circles by the book, The Well-Trained Mind, by Susan Wise Bauer and Jessie Wise, advocates and follows this model of learning. About the elementary ages, Susan Wise Bauer states, “In the elementary school years…the mind is ready to absorb information. Children at this age actually find memorization fun. So during this period, education involves not self-expression and self-discovery, but rather the learning of facts.” She goes on to say about the middle school years, “Middle-school students are less interested in finding out facts than in asking ‘Why?'” And her overall assessment of the focus of this educational model: “Classical education is language-focused; learning is accomplished through words, written and spoken, rather than through images (pictures, videos, and television).”

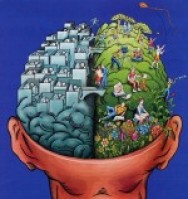

This order and focus of learning works for some people. It worked really well for me. I’m a strong left-brained learner, and a word and symbol focus early on is where my foundational strengths are. Short-term memory comes easily to me and spitting out facts makes sense. In fact, I was considered advanced in all three of the early focus subjects in school of reading, writing, and arithmetic. When concepts were introduced later in middle school and high school, I often found myself lost (i.e., math) and even a bit confused (i.e., history). What was going on here? It perfectly aligns with what I wrote about concerning the natural learning path for left- and right-brained learners based on their universal gifts.

I represented the natural learning path for left-brained learners. Schools prescribe to the left-brained pattern of learning. Because the majority of children attend school, this pattern of learning is used as the measuring stick for appropriate education. In fact, like the book that popularized classical education in homeschooling circles, it is considered the “superior” method of learning for a “well trained mind.” The problem is, this one learning model is not ideal for all learners. But when a child doesn’t perform in this learning environment, the left-brained measuring stick declares the child at fault. For instance, how often do I hear these stories:

I represented the natural learning path for left-brained learners. Schools prescribe to the left-brained pattern of learning. Because the majority of children attend school, this pattern of learning is used as the measuring stick for appropriate education. In fact, like the book that popularized classical education in homeschooling circles, it is considered the “superior” method of learning for a “well trained mind.” The problem is, this one learning model is not ideal for all learners. But when a child doesn’t perform in this learning environment, the left-brained measuring stick declares the child at fault. For instance, how often do I hear these stories:

- He can remember lines of a movie he saw once, but he does truly struggle to remember the spelling rule we learned 10 minutes ago, or what comes after 72.

- She’s bright and can memorize things easily, loves books, adores history and science, but she was resistant to reading more than a few sentences per page or writing more than a few words. Spelling was also not much fun to get through.

The good news is that there are other viable learning environments and methods and time frames that are well-suited for the different types of learners. Right-brained learners tend to focus on concepts first, in the early years of learning (K-5), always the first to ask, “Why?,” and then turn to facts in the middle school years and beyond. This means they need the opposite learning environment from their left-brained peers! What would that look like?

The good news is that there are other viable learning environments and methods and time frames that are well-suited for the different types of learners. Right-brained learners tend to focus on concepts first, in the early years of learning (K-5), always the first to ask, “Why?,” and then turn to facts in the middle school years and beyond. This means they need the opposite learning environment from their left-brained peers! What would that look like?

Let’s consider the first scenario above. It can’t be a memory issue, right, because he can remember lines from a movie he only saw once? But it could be a meaning issue (he doesn’t know why it’s important), or a visual learning preference (right-brained children learn best with pictures and images), or a lack of imaginative appeal difference (imagination being one of the two universal gifts of a right-brained learner). This is why right-brained children enjoy history, science, and geography. It’s highly visual, has an imaginative quality when explored through stories, hands-on experiences, and discovery methods of learning, and it’s remembering through association via long-term memory, the preferred memory path for right-brained learners. This parent was following perfectly the outline set by Susan Wise Bauer, but this is most likely a right-brained learner, who needs the opposite of the left-brained measuring stick.

We could then use this information about how right-brained children learn, and apply it to spelling. In the early years, right-brained children like to know why a subject is important to know. So, hooking it with expressing their ideas through writing would accomplish that. Understanding how a right-brained child comes to writing would come first, then. Many right-brained children begin to express their ideas through the creative outlets (drawing, building, acting, etc.) and through their play of imagination. If you ask them, young right-brained children will often tell you all about the story they are demonstrating. This was usually prevalent in the 5-7 year age range, and I could encourage this and listen intently to their stories and ideas. I might even write them down, thus, modeling how spelling is important.

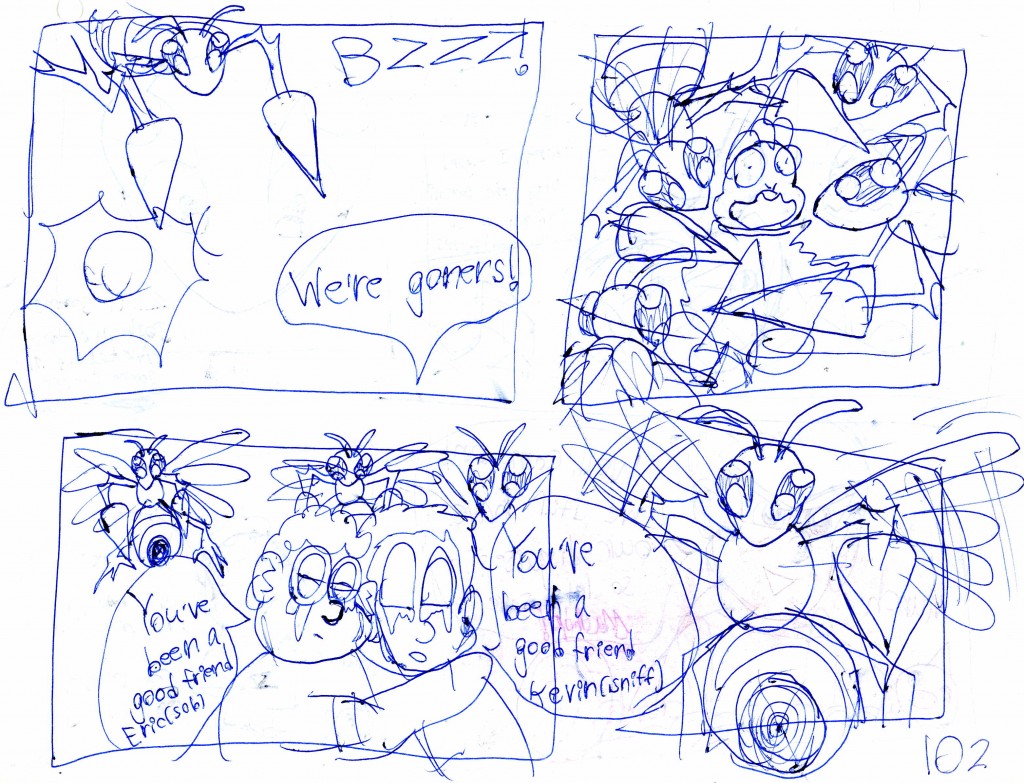

During the 8-10 year stage, I brought in resources that inspired their own creation of books and other physical products of their ideas. Comic books were common, making movies (using a camcorder or creating stop gap motion with LEGO), playing video games or computer on-line games, or coordinating play scenarios to act out with friends. As this periodic writing occured, spelling would surface. Some of my children used resources in asking others how to spell, and others didn’t and relied on invented spelling. But the reason to spell began. The more these creations were expressed, the more spelling practice occurred because the “why” came into play. For my short teaching moments in the 8-10 year stage, I might have them work from an appropriate spelling resource. Primary Phonics was a good fit for a few of my 8-10 year old children (visual, sight-word based, and self-directed).

It was during the 11-13 year stage that all my children figured out how to become proficient spellers. My writer daughter began using spell check as she wrote her stories, I helped my builder son understand the parts of words through Latin and Greek roots, and then worked through the auditory part with Natural Speller (modified to fit his needs), my next two worked through Target Spelling, and my last two are finishing Primary Phonics. Considering many right-brained adults are poor spellers, maybe honoring this natural path to spelling has merit being that all mine are good spellers who have reached the stage of fluent writing.

I found the second scenario interesting, because the child in question loves books, but doesn’t want to read the few sentences. That implies that reading is being structured. In other words, when the child gets to interact with books on her initiation, in her way, for her reasons, she loves them, but when it’s assigned, or approached from a left-brained vantage point, it becomes drudgery. I love these quotes I found about reading:

Reading, after a certain age, diverts the mind too much from its creative pursuits. Any man who reads too much and uses his own brain too little falls into lazy habits of thinking. ~Albert Einstein

A truly good book teaches me better than to read it. I must soon lay it down, and commence living on its hint. What I began by reading, I must finish by acting. ~Henry David Thoreau

So, so, so true! When I read a lot for pleasure, it’s for simple entertainment of my mind. If I read too much, I feel I haven’t actually fed my brain enough, so I put down reading to put my mind to work, as the Einstein quote suggests.

Over the past many years of parenthood, I’ve enjoyed self-help books, education books, and other venues of books that push my level of understanding and perspective. I often don’t make it all the way through a book before it’s inspired me to go do something. I love the Thoreau quote for this sentiment!

My experience with my right-brained children has shown this to be true. My oldest artist son tends to be an information book reader as he seeks out inspiration for portraying accurate depictions in his drawing. When he reads, it motivates him to act. He spends much more time thinking and doing based on his reading than the actual reading part. My writer daughter gets inspired in her own writing after reading other fantasy books. She would read a lot for a few months, and then write a lot for a few months. My builder son came up with new ideas for computer programming when he would study from computer manuals. My electronics son starts looking up more information on the internet after reading a biography. My theater son begins to create a storyline and costumes from a book or movie.

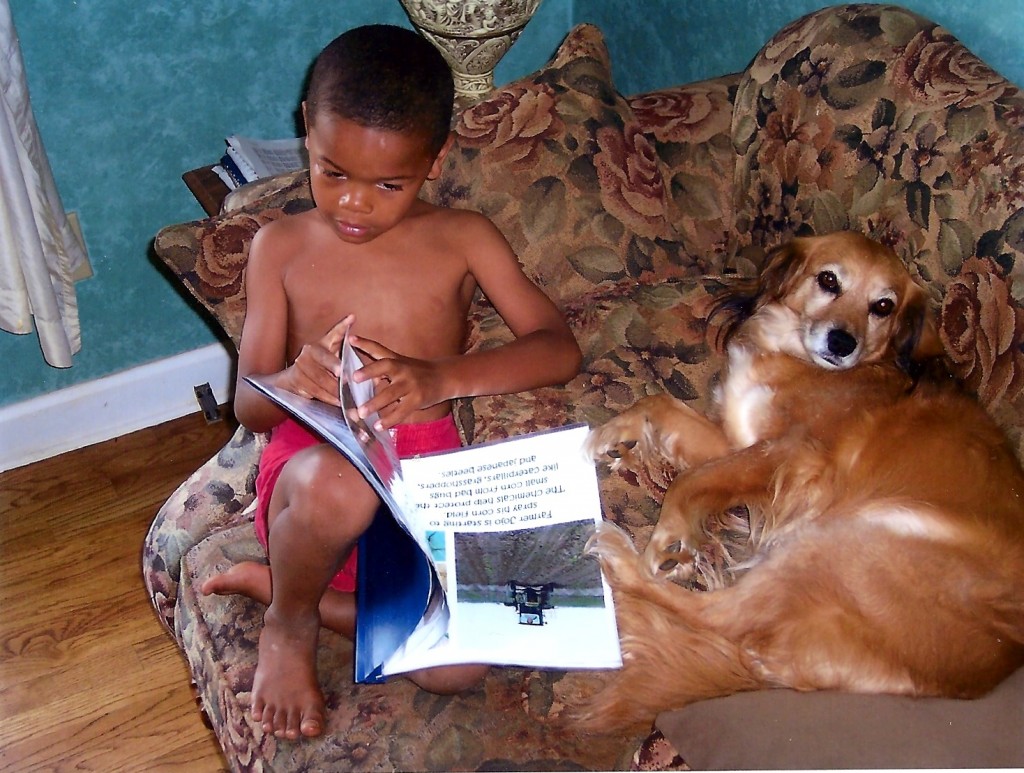

With this new perspective about how books can be a catalyst for inspiration, creativity, and active thinking and doing, this can occur at any time on the learning-to-read curve. Looking at pictures can inspire, listening to read alouds can motivate, and reading books of your own choosing can spark creativity. When a teacher breaks reading down into a skill to be developed versus a tool to be utilized, it may lose a lot of appeal to an innovative right-brained learner. Because I introduced books as a tool that enhances an individual’s own bent, it was useful starting at the earliest exposure. The positive relationship my children enjoyed with books for this reason was protected from the idea that books are only beneficial to an independent reader.

When each child showed they were ready to learn to read, I provided support for them to accomplish it. For those children who didn’t show readiness signs, I initiated learning-to-read opportunities consistently. Books were never avoided during this process as the great tool to enhance creativity and inspiration for each child that it is. Learning to read simply makes it more convenient to access the print tool because the child won’t have to find an available reader.

In the meantime, all the other interests and natural strength subjects for right-brained children (science, geography, cultures, mythology, nature, history, and animals) were a rich part of each child’s learning life. Books were one tool. Learning to read was one eventual goal, just like learning more about the culture of Japan, or how to grow a garden, or doing a science experiment, or enjoying a biography read aloud.

Science, geography, history, nature, mythology, animals, and cultures are common early subject strengths for right-brained children.

It’s really about shifting our perspective on how we inter-relate with certain subject areas with our children. So many times, our left-brained measuring stick is interfering with the natural right-brained learning process. Cassidy shared her son’s success after she shifted her perspective:

Cindy, I am so thankful for your book. It has allowed me to relax as a parent and teacher. My boys are so much happier and I am too. I didn’t realize how much I was stressing us all out. I am rereading the book right now and I am in awe. My son is 8 years 4 month. As I read about reading and pre-writing, I am seeing him do exactly what you describe in the book. He is the kid who hated writing/typing. He loves to write stories so I would encourage him to try typing the words out; it always resulted in tears. This week he wanted to type a message for a friend on an online game. I had just read about spelling in the book, so I just spelled the words for him. He typed 2 sentences!!! Later in the week, I saw some of those same words written under his art work!!! He has always been drawn to comic books, but I didn’t see the value in them until I read your book. We have been reading them non-stop since. He sat down this morning and started reading Shel Silverstein to his little brother. He started categorizing the apps of our iPad. He asked me to spell a few things, but then sought out a reference. I am just blown away!!! All these years I felt like I was spinning my wheels, and he’s picking all this up within a week! Wow! Thank you just doesn’t feel like enough!

Is there really only one right way to learn the various subjects? Why are we more concerned that our child know what a noun is first (learning by memorization) versus learning the names of countries and continents based on a child’s interest in various animals (learning by association)? Is it more important to know that 2+2=4 (facts) or that it actually isn’t always true (2 horses + 2 tractors does NOT equal 4 animals) (concepts)? And how many of your children could navigate the computer (picture-based) even before learning to read (word-based)? Mine did! Using the left-brained measuring stick to determine the path for learning for all children is narrow-minded, inaccurate, and even damaging. There are brilliant right-brained children waiting to thrive in a well-matched right-brained learning environment that requires its own measuring stick. There is a right side of normal!

Question: How has the left-brained measuring stick interfered with your right-brained child’s natural learning path? What did you do to help?

Pingback: Comparing Apples to Oranges | The Right Side of Normal

Pingback: The Gift of Three-Dimensionality We Call Dyslexia | The Right Side of Normal

Pingback: Your Child Might Be Right-Brained If … | The Right Side of Normal

Pingback: An Introduction to the Creative Right-Brained Learner | The Right Side of Normal