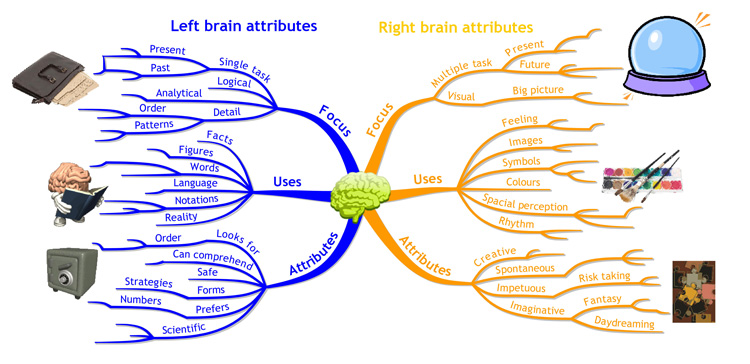

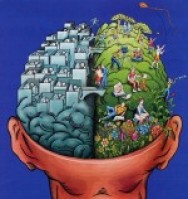

There’s still controversy surrounding the idea of a right-brained/left-brained learning style continuum. Most professionals who want to steer away from it argue that the brain is a complex organ that interrelates seamlessly and certain attributes can’t be simply compartmentalized into one side or another. I agree. I don’t want to oversimplify how the brain works. I share my perspective in Chapter One in my book, The Right Side of Normal:

Although controversy continues regarding the labeling of people as left-brained or right-brained, I have noticed, as have many experts (see Chapter Two), an easily recognizable pattern of learning and temperament traits that frequently go together. For instance, when I describe these traits (see Section Two) at conferences, I see whole audiences nodding in recognition. Inevitably, various individuals approach me and say, “You described my child to a tee” or “Have you been looking in our window?” This can’t be coincidence. Whether proven by current studies or not, there’s ample anecdotal evidence that supports there are time frame, temperament, and gift/strength differences based on brain processing preferences.

Being left- or right-brained dominant doesn’t mean we only use half our brain. Billions of bits of information per second can travel along the nerves that connect the two hemispheres, so naturally there’s communication between the hemispheres. I’m simply talking about the brain processing preferences that each of us is biologically born to favor. With those preferences come the traits that stem from the specialization found in the left or right side of the brain.

The answer to why I choose to use the holistic label of right-brained learner can be explained in the part versus whole learning traits. When we use a holistic label, such as right-brained learner, the part labels make more sense in the grand scheme of things. Let me explain:

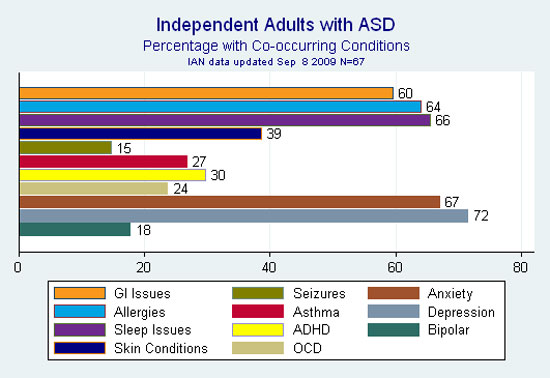

In the autism world of diagnosis, there are certain “givens” that come with this difference. Most will have ADD components, most will have a sensory difference, most will have OCD-like attributes, most will have APD, and most will have anxiety-related symptoms. These things are typically not diagnosed separately. I addressed the sensory differences with my sons with autism in a certain way based on the fact that it was autism-related. Some children with autism will have other types of differences, but not all, such as seizures, mental retardation, or giftedness. Understanding the overall holistic label of autism helps me more effectively know how to address those part labels that often attend the bigger difference.

This same thing is true about the right-brained learning style. There are certain things that come with this learning style, such as many being later readers, not being proficient early with math facts, being poor early spellers, having extraordinary imaginations, being highly sensitive, or enjoying creative outlets. Some right-brained people can have added features like being gifted, or having trouble with right-brained strengths (NVLD), or autism. But there are part labels, such as all the “dys”abilities (dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia), APD, and ADHD in particular that may be viewed differently if first sifted through the holistic right-brained label.

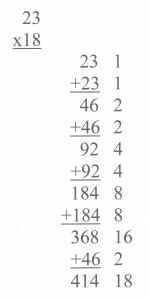

One example is right-brained people prefer learning concepts before facts. They also have a stronger long-term memory by learning through association rather than short-term memory through the use of memorization. With this in mind, it makes more sense that math will be learned conceptually first and facts follow through meaningful use. (Right-brained learners are also picture-focused before symbol focused. See this great example in action.) It also makes sense that spelling will develop after learning to read and during the meaningful function of writing that develops between 11 and 13 years old. Another example is right-brained dominant people often prefer the visual or kinesthetic route to learning, so sometimes having a weaker auditory input will make sense. Recognizing that hooking the auditory input with one of their strength inputs may result in competency. These are the types of perspective shifting that can occur for these learners. With the holistic right-brained label understood first, better suited learning strategies will be applied, right-brained learning will be supported, and right-brained children will show how they learn and grow naturally as they thrive in a well-matched learning environment.

One example is right-brained people prefer learning concepts before facts. They also have a stronger long-term memory by learning through association rather than short-term memory through the use of memorization. With this in mind, it makes more sense that math will be learned conceptually first and facts follow through meaningful use. (Right-brained learners are also picture-focused before symbol focused. See this great example in action.) It also makes sense that spelling will develop after learning to read and during the meaningful function of writing that develops between 11 and 13 years old. Another example is right-brained dominant people often prefer the visual or kinesthetic route to learning, so sometimes having a weaker auditory input will make sense. Recognizing that hooking the auditory input with one of their strength inputs may result in competency. These are the types of perspective shifting that can occur for these learners. With the holistic right-brained label understood first, better suited learning strategies will be applied, right-brained learning will be supported, and right-brained children will show how they learn and grow naturally as they thrive in a well-matched learning environment.

If we use the part label, dyslexia or dyscalculia, for instance, to categorize a child, we’re missing a big component of not only strengths, but the context in which this difference exists. Is it actually a weakness, or a scope and sequence difference? And if we find trouble with reading or math acquisition within the natural right-brained learning development, do we have a better idea how to help based on what we know about how they learn best? By bringing these part labels under the  influence of the holistic label of right-brained learner, questions can be better answered. Many parents who have made this shift have experienced their child flourishing and thriving in the natural learning development best suited for right-brained children. Are we missing the forest for the trees when we use part labels outside of the context of the whole label? I think so. I would love to see research on those who use a right-brained scope and sequence on right-brained children.

influence of the holistic label of right-brained learner, questions can be better answered. Many parents who have made this shift have experienced their child flourishing and thriving in the natural learning development best suited for right-brained children. Are we missing the forest for the trees when we use part labels outside of the context of the whole label? I think so. I would love to see research on those who use a right-brained scope and sequence on right-brained children.

Pingback: Right brain and dyslexia - Dyslexia HeadlinesDyslexia Headlines

Pingback: Let’s Pretend our Society Embraces the Right-Brained Learning Information… | The Right Side of Normal