A little while ago on my Homeschooling Creatively list, a homeschooling mother came on and offered a free worksheet for curriculum planning. There were several glaring things on her worksheet that opposed what we talk about on the list regarding the way right-brained children learn.

First, all the subjects were listed with typical age notations in parentheses. We talk exhaustively about how right-brained children typically learn at a very different time schedule than what you see in school. If a parent felt a need to put together a curriculum for a right-brained child using the age guidelines found in a traditional school scope and sequence, frustration would follow. Further, school tends to be weakness-based. For a strengths-based curriculum, how a parent plans it looks very different.

First, all the subjects were listed with typical age notations in parentheses. We talk exhaustively about how right-brained children typically learn at a very different time schedule than what you see in school. If a parent felt a need to put together a curriculum for a right-brained child using the age guidelines found in a traditional school scope and sequence, frustration would follow. Further, school tends to be weakness-based. For a strengths-based curriculum, how a parent plans it looks very different.

The second glaring idea wrong on the worksheet was that a line was drawn at the bottom of the page with certain subjects listed under it that indicated these subjects could be postponed or skimmed if stress or time become an issue. The problem was that most of the subjects listed under the line were strengths of a right-brained learner! Subjects like history, geography, nature, art, and music. It just proved to me how prolific the conditioning we have as a society to value the three Rs: reading, writing, and arithmetic, and devalue what we would refer to as “extra-curricular” with music, art, and theater, or elective-based subjects such as history and social studies. In a strengths-based learning model, what goes under that line may prove to be very different.

In each of the four section headings of my book, The Right Side of Normal, I share various culturally-based beliefs about learning and education and then help the readers shift perspective about it when held up to the light of a  strengths-based learning model. A couple of those ideas I just high-lighted above in response to the free worksheet about curriculum planning shared on my list. In order to have faith in a different way of approach-ing learning, we may need to deschool our thinking about learning from that found in school. The scope and se-quence found in school isn’t the only way to learn, or even the best way.

strengths-based learning model. A couple of those ideas I just high-lighted above in response to the free worksheet about curriculum planning shared on my list. In order to have faith in a different way of approach-ing learning, we may need to deschool our thinking about learning from that found in school. The scope and se-quence found in school isn’t the only way to learn, or even the best way.

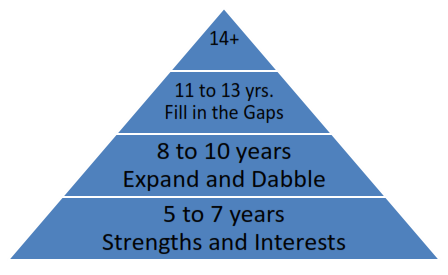

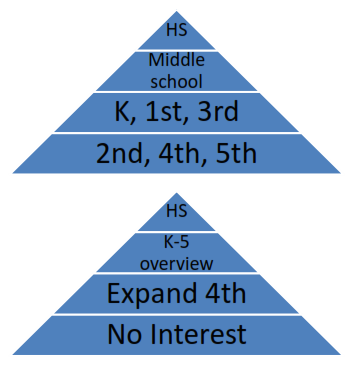

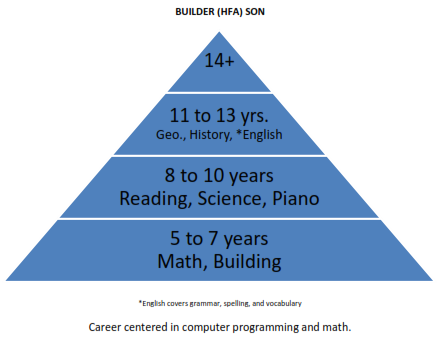

To understand my strengths-based learning environment, you may want to read up on my Collaborative Learning Process. This was my translation of what happened in our learning lives. What I did to create an individualized curriculum changed based on the stage of the child. How I want you to envision the process is in the form of a pyramid. The foundation is in one’s strengths. The next layer up is when a parent or educator expands a child into a few new areas. And the top layer is when a parent or educator fills in the gaps with the child.

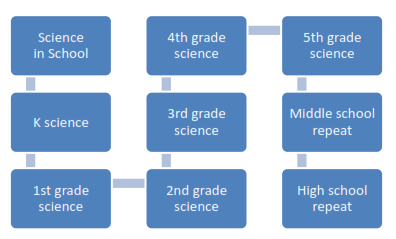

I do believe in having exposure to most of the subjects. I just don’t agree with how school goes about it from a standardized manner. School takes a whole subject, such as science, and chops it up into chunks and divides it between the elementary age levels, a part-to-whole method. Then, they take that same science topic and divide it into three chunks for each of the middle school years. In other words, everything is repeated again, but done faster. And then the same division is meted out in the high school years, with more depth being covered. The method school engages in is offering a little of everything every year, and hope some of it gets absorbed. If not, no worries because it’ll get repeated in middle school, and again in high school.

What does the planning of science look like in a strengths-based open-ended individualized learning environment? If you have a child who enjoys science, which can be common for a right-brained child, you may find he has a focus for it in the early years of 5 to 7. But, he may be more interested in magnets, and then motion, and some dinosaurs, nature and animal studies, finishing with weather. Depending on the school, those subjects in science could be a bit in 2nd grade, 4th, and 5th. Just by interest, your child covered a lot of these areas. It doesn’t matter if he didn’t write a report on it; he was interested in the ideas and understood as he explored through experiments, for instance. As this child progressed to the 8 to 10 year range, he scales back into the dabbling realm, and so you bring in electricity and DNA to play around with. Because you have a child who had a science mind, in the 11 to 13 year stage, you could set him up with a middle school level science curriculum that covers all the elementary subjects where he will pick up any missed gaps.

But let’s say you don’t have a science minded young person. Instead of science in the 5 to 7 range, she was definitely into nature and animals, but expressed herself more through writing and telling stories. She would sit in on experiments the family explored, but didn’t pursue anything on her own. During the 8 to 10 year stage, you dabble in some related ideas such as a plant study through nature hikes, and a Science with Mad Dad exploring general science ideas. Now that middle school arrives without a lot of interest or focus on science, yet, as noted, there were incidental and expanded opportunities, so a general aptitude is there, you find a resource that covers much of the elementary science topics at about the 3rd-5th grade level. Why this level instead of middle school level? Because if a person really grasps the concepts of the various science areas, such as body, nature, planets, magnets, electricity, etc. at the upper elementary levels, she can be prepared to go deeper during high school at the regular high school level. This is because basic aptitude of the subject meets maturity and overall intellect to meet the high school level science resources.

I found many school subjects followed this pattern: science, history, geography, and social studies, for instance. Then there is the other category that includes reading, grammar, spelling, vocabulary, and writing, for instance. The scopes and sequences found in school arbitrarily create some kind of systematic method to learning these things, when, in fact, each is most often learned through natural means. Reading aloud to my children was the core for much of  these English-related subjects. Hearing a good story inspires a child to want to read, helps them hear the patterns of writing and good grammar, and exposes them to a variety of vocabulary. It also inspires a child to tell his own stories, whether orally, through a technology medium, or by making their own simple first books. First books can encompass stapling pages together, drawing comic books, creating pop-up books, or putting together silly ideas such as a creature book. This naturally brings in spelling and writing. When the appropriate developmental time arrived, each of my children focused on a one to two year learning boost for each of these topics to catapult them into proficiency.

these English-related subjects. Hearing a good story inspires a child to want to read, helps them hear the patterns of writing and good grammar, and exposes them to a variety of vocabulary. It also inspires a child to tell his own stories, whether orally, through a technology medium, or by making their own simple first books. First books can encompass stapling pages together, drawing comic books, creating pop-up books, or putting together silly ideas such as a creature book. This naturally brings in spelling and writing. When the appropriate developmental time arrived, each of my children focused on a one to two year learning boost for each of these topics to catapult them into proficiency.

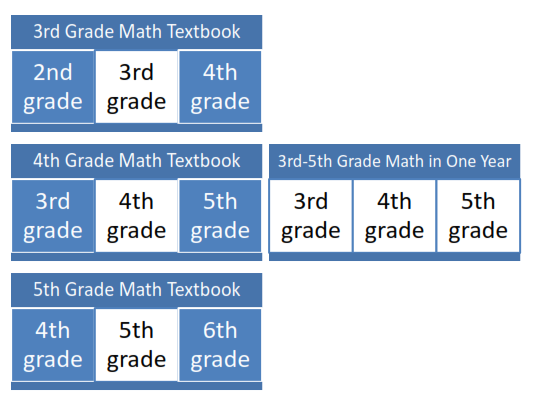

The meting out of yearly doses of each of these subjects is created to measure and fulfill schooling purposes to fill learning time. It’s not how these subjects are meant to be learned naturally. This is also how math is pursued in school. Textbooks are usually used to learn math. I explain to parents that only one-third of the material of each textbook subject is new information. The first third of a textbook is review from the previous year, the next third is new material, and the next third will be repeated at the beginning of the following year. What strengths-based learning does is take all those one-third parts and put them all back together into it’s whole form. When the timing is right for the individual to learn the material, it’s typically learned in one whole chunk, over a one to two year period.

The pattern of math learning for many of my children typically consisted of playing around with math ideas in the 5 to 7 year range through videos, games, puzzles, mazes, and other life math opportunities. In the 8 to 10 year range, each dabbled in different ways in learning adding and subtracting, time and money, and other general math ideas. It wasn’t usually until about 11 years old that a formal program was used in order to learn the rest of math, typically utilizing a 1.5 to two-year jump per year, usually being able to start with 3rd grade level math. So, at 11, it was 3rd-4th grade; at 12, it was 5th-6th grade; at 13, it was 7th-8th grade; and so 14 began algebra. Because we’re strengths-based, only the children who were going to pursue a maths-needed career pursued higher math beyond 1st year algebra and geometry.

To go back to my overall strengths-based open-ended individualized learning environment, subject learning occurred based on the individual child’s gifts, strengths and interest. If it’s a strength subject, it will be pursued quite young and researched throughout their learning lives. It will get expanded on during the dabble stage and more fully engaged in during the fill-in-the-gaps years. If it’s a dabble subject, a handful of concepts will be taught or learned each year through their preferred learning style. In this way, there’s not a lot of waste in the learning process. And during the fill-in-the-gaps stage, more formal resources are ofren used since the stage is more conducive to focused work. Even though many subjects are learned in an integrated manner, each subject will have its time in the limelight of study, in it’s respective time for the individual preference, interest, and gift.

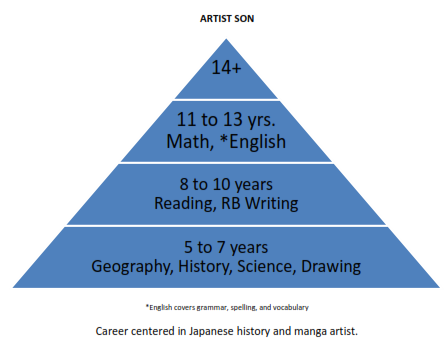

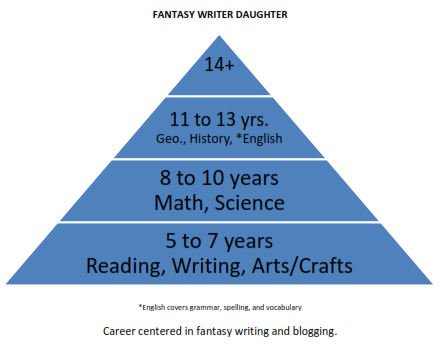

Let me give you examples based on my first three children:

Let me choose my artist son’s lack of interest in math. During the 5 to 7 year stage, he had plenty of opportunity to incidentally pick up math concepts. He could do all of the kindergarten concepts, and did a lot of mental math for the first grade focus in math. During the 8 to 10 year stage, I would pull him aside for short teaching moments (about 15 minutes at a time) and show him carrying and borrowing for addition and subtraction of larger numbers. Incidentally, he picked up on time and money and other extraneous math concepts. I made up the math problems to work on using manipulatives, but something like Math U See or Math on the Level operate similar to what I did. At 11 years old, I taught him multiplication through the first Saxon book (at the time), and then moved him to a concept-based math series called Real Math. At 14, he took an algebra class with four other homeschoolers.

Let me choose my writer daughter’s strong interest in writing to share how a gift is developed. During the 5 to 7 year range, she taught herself to read at age 5 by being intrigued by the words on the page as I read to her. (I wouldn’t know she learned to read until she was already fluent when I noticed at age 6!) She would copy the words from books into her own “books.” She loved to tell stories. No formal lessons were ever given. When she entered the 8 to 10 year time, she started to keep a journal, wrote short stories and entered story contests through the newspaper, continued to orally tell her stories and make movies of her adventures on the camcorder, and loved books that were descriptive, like poems. Once she entered the fill-in-the-gap stage, her short writings suddenly were extending until she was writing novels. Before that, she enjoyed doing writing assignments from unit studies on other topics, or writing up what she knew about her favorite topics of animals. She wanted to learn more formally English-related topics such as grammar, spelling, and vocabulary to better her writing.

For my builder son, I’ll show what a subject started in the dabble stage looks like with science. In the strength stage, his focus was mainly things he could manipulate and that had a spatial component. Being he was diagnosed with autism, it makes sense he wasn’t that aware of his surroundings that incidental science tends to incorporate. He also had no interest in books, whether joining read alouds or looking at them on his own. He could easily use LEGO instruction booklets, though. In the dabble stage, he noticed that science experiments were a lot like building things, so he became interested. He enjoyed the electronics side of thins as well, such as learning to build a phone, for instance. We consistently helped him plug into various science options along these lines. Once he hit the fill-in-the-gaps years, I found some formal resources that covered the various science subjects throughout elementary, whether it was about weather, plants, classification, body, and so forth. By 14, he started the four course Apologia science series before entering community college.

Isn’t it absolutely fascinating that each of my children’s preferred interest in their earliest years (with no direction or prompting from me) ended up being the category of their career paths? When I wrote out the stages of my first three children some years ago with how they progressed through the various subjects of school, I was pleasantly shocked to discover the foundational first stage strengths connection to their future careers. Truly, I believe MOST people tip their hand at a very early age what their strengths are, if we would get out of their way so they could show us. There really IS time enough for learning all the subjects sufficiently for proficiency. I believe strongly that the format in which I instinctively structured our learning environment is a primary reason each of my children love to learn, found their passion and subsequent purpose for their gifts, and understand the way they learn so they can be self-advocates.

Question: What are some of the reasons it’s hard to let go of the standardized, piece-meal version of learning each subject in bite-sized chunks versus developing the faith that there is a developmental time to learn each subject whole based on one’s gifts, interests, and need?

Pingback: Unschooling UnDefined | The Right Side of Normal

Pingback: A Different Process and Product |