Linda Asks: How can being accused of being “lazy”, “unmotivated”, and “irresponsible” possibly feel BETTER to a person who has no control over those traits than being diagnosed with a “learning disability” that explains that these traits (disorganized, spacy, unable to complete tasks, etc) are genetic and innate? No one blames and hates him or herself for being “born this way” (to quote a popular song). Once a child knows that s/he has dyslexia, doesn’t that free him/her from the pressure to read by a certain age?  Linda makes an important point, and I want to take the time to explain my perspective. It’s not good to be called “irresponsible,” “lazy,” or “unmotivated.” It’s equally not good to be called “disabled.” Aren’t all these labels crying out, “What’s WRONG with you? Get it together and/or fix it!”

Linda makes an important point, and I want to take the time to explain my perspective. It’s not good to be called “irresponsible,” “lazy,” or “unmotivated.” It’s equally not good to be called “disabled.” Aren’t all these labels crying out, “What’s WRONG with you? Get it together and/or fix it!”

It’s my belief that you are absolutely correct when you say a child can’t help it if they’re spacey, disorganized, or unable to complete tasks because they’re born that way. We can help parents and educators view these children differently by helping them understand and honor how brain processing preferences create these differences.

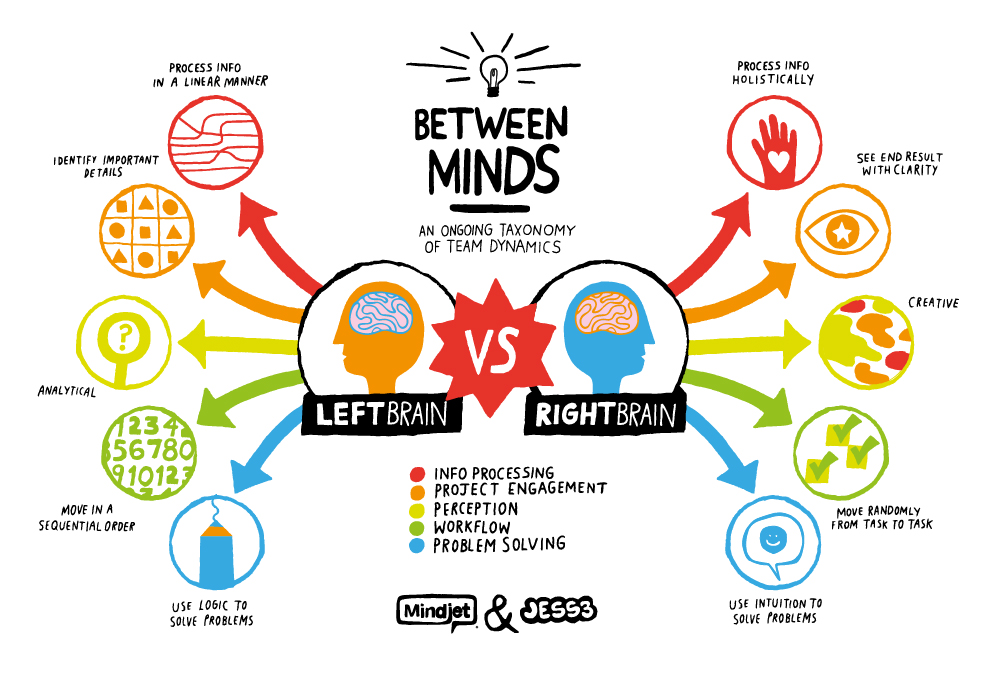

I want parents and educators to understand that it’s normal for right-brained learners to have a variety of differences or preferences, such as memory preferences, attention preferences, subject preferences, input modality preferences, etc. Let me repeat that in current perspectives: I totally know that right-brained children can be spacey during a lecture, disorganized with assigned tasks, not get their math facts in third grade, and not read in first grade. It’s all true!

What we’re not understanding as a nation is that certain learning environments and particular time frames are conducive to supporting each type of brain processing preference. Schools as they exist right now do not support the right-brained processing preference. They support left-brained learners. In fact, schools right now exacerbate these right-brained differences and turn them into problems.

What we’re not understanding as a nation is that certain learning environments and particular time frames are conducive to supporting each type of brain processing preference. Schools as they exist right now do not support the right-brained processing preference. They support left-brained learners. In fact, schools right now exacerbate these right-brained differences and turn them into problems.

The key to honoring the way each child processes information is through offering a strengths-based developmental path to learning. Let me show you what we’re currently doing that results in being diagnosed with a learning disability as the solution, and what it would look like if we offered a strengths-based developmental path to learning, not as a solution, but as a natural unfolding process that respects individuality:

The Current Situation for Right-Brained Learners:

Each child goes to school, and/or each parent is influenced by school for the child’s learning life. There is one, I repeat ONE, scope and sequence in school. Each and every child must navigate that one way and time to learn. For instance, the focus in first grade is reading, writing, and arithmetic. If these are not your subject strengths, and instead you are more creative-oriented, and would love history and animals and cultures, you may look spacey.

There’s one curriculum for each subject; I repeat ONE. If the writing curriculum has you handwriting sentences down, but you’re developmentally at the stage of picture-based thinking because of your brain processing preference, you may look like you have a glitch in your brain that can’t organize your thoughts. Yet, let you tell your stories going on in your head aloud to a person, or act out or draw out, or use puppets to show your stories, you’re brilliant.

There’s predominantly one way of presenting information, usually auditory and board work; I repeat, ONE. If the teacher is at the board showing a new word to learn and everyone is to repeat the letters as she points to it, but your dominant input modality is kinesthetic, you may be accused of not being able to sit still, or that you’re being disruptive in class as you use your pencil as a drum on your desk. But have a giant world map on the floor and be given some visual cards to match to each country’s outlined location, or have country cards to deliver on your pretend bike to each corresponding continent mailbox it goes to, you may shine.

There’s predominantly one way of presenting information, usually auditory and board work; I repeat, ONE. If the teacher is at the board showing a new word to learn and everyone is to repeat the letters as she points to it, but your dominant input modality is kinesthetic, you may be accused of not being able to sit still, or that you’re being disruptive in class as you use your pencil as a drum on your desk. But have a giant world map on the floor and be given some visual cards to match to each country’s outlined location, or have country cards to deliver on your pretend bike to each corresponding continent mailbox it goes to, you may shine.

There’s predominantly one way of remembering information, short-term flashcard type memory work; I repeat, ONE. The teacher sends home a list of spelling words for you to memorize…write each one out five times, or drill with your parent to memorize them. You may be accused of being unmotivated when your parent has to force you to finish writing the word five times because writing isn’t the way you process information, or get frustrated when you don’t work hard enough at drilling, even if it’s because you learn better through long-term memory strategies. If you were involved with science experiments where various science vocabulary words were described throughout the process as you experienced it and explored the cause and effect created, it may astound others to see how easily you remember by association that specialized vocabulary.

There’s one right time to learn something, like reading by 6 years old; I repeat, ONE. As hours and months of phonics training goes into the mind of a creative, picture-based right-brained 5-year-old child’s mind, there’s no where to stick because the developmental time for processing words hasn’t yet arrived for this particular child. You may be accused of having a learning disability And yet, you can build amazing LEGO creations for hours, or dance like an angel.

The Strengths-Based Developmental Learning Path for Right-Brained Children:

In the preschool years of 3 to 5 years old, a strengths-based developmental learning path would have all children benefit from the research and reinstate play as the core requirement of childhood. Nurturing familial relationships would be valued as the emotional foundation for future independence and confidence. Being in nature, going to park days, jumping in puddles, riding bikes on trails, playing childhood games, and exercising big motor movements would be the norm.

I challenge anyone to find one study or piece of research that states that pursuing academics sooner, especially in the preschool years, is in any way advantageous. It’s a crime that child developmental research is completely ignored as we raise children in our nation to be more academically minded when brains are just not developmentally ready for it. Yet, we look for signs and symptoms such as inattention, vision issues, or poor symbol processing when it’s not even developmentally appropriate.

From 5 to 7 years old, a strengths-based developmental learning path would have all children create a strong foundation in their strength areas based on their brain processing preferences. That means right-brained children will have access to all the creative outlets (art/photography, cooking/gardening, dance/music, building/electronics, theater/showmanship, fashion/sewing, math/numbers, puzzles/mazes, and video games/computers). They will also get to enjoy their early subject strengths of science, animals, cultures, geography, history, mythology, and any other creative, pictorial-based subject that interests them. It would be hard pressed to find a spacey, disorganized, unmotivated child in this setting. Each plays up the strength of a creative learner by engaging their foundational gifts of high imaginations and pictorial thinking.

If strengths are valued and promoted at this appropriate developmental stage of learning, we won’t be looking for “signs and symptoms” that occur because of a mismatched environment. No one would be called lazy or unmotivated because the learning environment would match the activities that promote their  foundational gifts that prepares them for the next developmental learning stage. Plus, if we parents and educators know about the brain processing preference developmental learning stages, if we see signs of struggle or differences, then the first thing we would try is to change the learning environment to fit the child; not the child outfitted with a label to fit the environment. Especially when they are so young and just developing their foundation.

foundational gifts that prepares them for the next developmental learning stage. Plus, if we parents and educators know about the brain processing preference developmental learning stages, if we see signs of struggle or differences, then the first thing we would try is to change the learning environment to fit the child; not the child outfitted with a label to fit the environment. Especially when they are so young and just developing their foundation.

And so I could go on to the next stage, and the next stage of learning development for those who were born with the right-brained processing preference. I’ve written it all out in my book, The Right Side of Normal, in Section Three where I take each subject and show how and when many right-brained children learn those things. I’ve shared the strengths-based developmental learning process in my book, and quite well in my blog post here (still by far my most popularly read post). In my book, in Section Four, I also take each learning disability label common to the right-brained learner and show how each sign and symptom is actually a normal right-brained attribute mismanaged in the wrong learning environment.

Are there traits of a right-brained learner that can cause them trouble and need to be strengthened? Absolutely. When is that best accomplished? If the strengths-based developmental learning path is honored all the way through the integration stage in order to capitalize on the needs of each brain processing preference, an enormous amount of progress can be made in any weak areas that are left starting in the 11 to 13 year stage. Not only are young people more able to be partnered with after this crucial brain shift occurs, but all the information gleaned about how that individual child learns can be most fully utilized to his advantage. In other words, he can use his strengths to lift his weaknesses.

Do I believe there is a small percentage of people who could truly be learning disabled? First, we’d have to define what we mean by disabled, as well as words that might be more fitting like disadvantaged, or a weakness. For instance, for those labeled with dyslexia, do they have a weakness in reading, a disadvantage in reading, or truly a disability in reading? Since I’m a parent of a 20-year-old son who is intellectually disabled, who has no ability to compensate for his inabilities enough to live independently…ever, I think there’s a huge difference.

And words matter.

I would much rather have someone labeled a right-brained learner through understanding the traits and strengths of a right-brained dominant person and recognize those early on and match the child up with the right learning environment that will optimize his natural bend. By doing this, no name-calling would be necessary, no self-doubt would occur, and a disability label wouldn’t be needed to justify a natural born bend.

Right now, we expect everyone to look the same, and we wait for negative symptoms to arise that denotes the child doesn’t fit. The current response is then to say something’s wrong with the child, not that they just process differently from the current environment.

What if, instead, we recognize the positive traits of each brain processing preference early on allowing each parent, educator, and child to understand and honor all that goes with it, including particular strengths and gifts, certain preferences in learning methods and time inclinations for acquiring various subjects, and even a propensity for certain weaknesses. Knowing why a child learns what he learns when he learns it based on brain processing preferences changes everything!

Question: How would it feel differently to identify your child as a right-brained learner early on, with its inherent strengths, methods, time frames, and weaknesses, versus identifying your child as learning disabled?

5 responses to “My Readers Ask: Doesn’t a Learning Disability Label Make a Child Feel Better About Himself?”