Most parents and educators emphatically believe that the best, most reliable path to learning to read is through a systematic teaching of phonics. Even remedial dyslexic programs tend to be based in phonics. As I’ve said here before, is there really only One Right Way to reading?

Frank Smith, in his book, Reading without Nonsense, was one of the best, well, no-nonsense views on how children learn to read. In my book, The Right Side of Normal, I quote Smith as he shows how phonics is overrated in effectiveness:

An ongoing debate surrounds phonics versus sight word, but when the way people read is analyzed, a strong sight word base prevails. In Reading without Nonsense, author Frank Smith reminds us that it’s even difficult for computers to be programmed for text-to-speech. Smith illuminates the reason:

Here are 11 common words in each of which the initial HO has a different pronunciation: hot, hope, hook, hoot, house, hoist, horse, horizon, honey, hour, honest. Can anyone really believe that a child could identify these words by sounding out the letters?

Smith clarifies when he says, “Phonics will in fact prove of use―provided you have a rough idea of what a word is.” This is why I advocate what I call a “phonics program behind a sight word approach.”

I agree. I don’t see it as a debate between phonics or sight words. I strongly believe both are needed. And I strongly believe that it doesn’t matter which starts first, but it should be based on the learning preference of the child.

I agree. I don’t see it as a debate between phonics or sight words. I strongly believe both are needed. And I strongly believe that it doesn’t matter which starts first, but it should be based on the learning preference of the child.

The Intelligence Factor

Some parents or educators will swear that if a young child (between the ages of 2 and 4) begin the gold standard phonics teaching program, all children will learn to read painlessly and early. What I know about how brains work just doesn’t support this premise. And it causes many parents to question the intelligence of their child.

I have two children who taught me, in retrospect, that readiness to learn to read has nothing to do with intelligence. My fourth son is diagnosed with severe autism. My oldest son is gifted. I relate in my book, The Right Side of Normal, how my younger son learned to read, and how his particular brain strengths helped him to learn to read compared to his older brother:

This son spent hours a day with alphabet puzzles, alphabet books, and alphabet toys. He knew his alphabet before he was two years old. The same was true of his numbers. He seemed to positively respond to the predictable pattern of letters and numbers. On the other hand, hearing words spoken to him was confusing, unpredictable, and frustrating. Books with patterned letters that created words were a source of comfort, pleasure, and predictability.

My fourth son was four years old when it occurred to me. I’d been trying to help him learn to speak and understand the spoken word, but it was slow going. He often misunderstood what he heard because of poor auditory input processing. Why not see if he could learn to read? If he could better understand the written word, would that help him understand what he was hearing of the spoken word? We could write things down as we spoke them. I saw that letters made sense to  him, so maybe words would also. I bought a new flap book alphabet book and made picture flashcards of the words in the book. Matching was his favorite way to learn, so I helped him learn these words separate from the book. He picked them up quickly. There were three words per letter, and I taught him through the letter H. Then I showed him the book containing his flashcard words and had him start reading it with his new knowledge. His eyes lit up as he realized he could learn to read his alphabet books without someone having to read to him. His reading took off using these learning strategies.

him, so maybe words would also. I bought a new flap book alphabet book and made picture flashcards of the words in the book. Matching was his favorite way to learn, so I helped him learn these words separate from the book. He picked them up quickly. There were three words per letter, and I taught him through the letter H. Then I showed him the book containing his flashcard words and had him start reading it with his new knowledge. His eyes lit up as he realized he could learn to read his alphabet books without someone having to read to him. His reading took off using these learning strategies.

So many of us assume high intelligence (IQ) equates to early learning. And yet, this fourth son’s IQ tests in the mentally retarded domain. It wasn’t his intelligence factor that helped him learn to read at age 4. It was his strength in patterns and his love for letters. These strengths―and his readiness based on those strengths―helped him learn to read at age 4. His oldest brother has an IQ in the gifted domain. His strengths are in imagery and creativity. These strengths and his readiness based on those strengths helped him learn to read at age 9.

Sight Word Reading

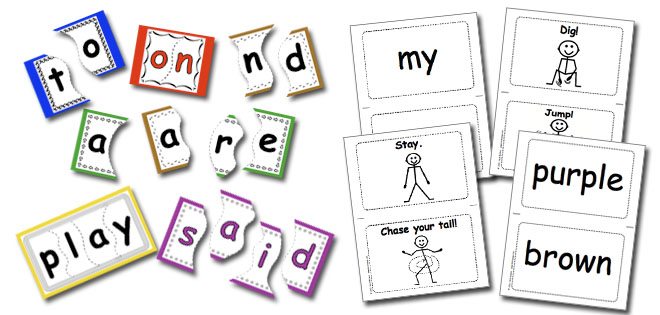

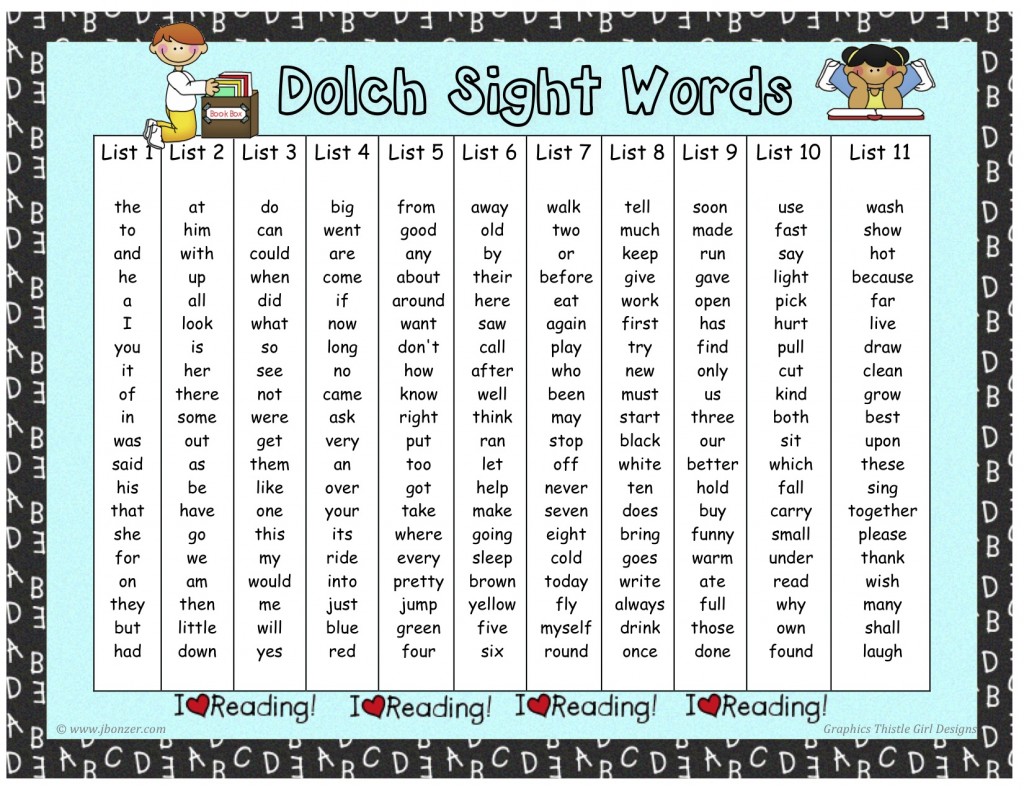

I think many parents, and maybe even educators, think of the Dolch words when they think of sight words. Dolch words consist of the top 220 high frequency sight words that can’t be learned by pictures or phonics. For right-brained children, learning to read with sight words means something very different. In fact, the explanation is in the definition of Dolch words.

A right-brained reader learns to read by translating words into pictures. This is because of their highly visual nature. This high level of visualization ability is what helps a right-brained child learn to read and comprehend what they read. These readers will more likely learn to read “giraffe” before any of the Dolch words because it can be visualized. Thus, it is a huge mistake to begin with Dolch word readers to teach a right-brained child to read by sight words. It is much better to start with reading nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and any other words that have pictures. They can start by reading alphabet books or children’s picture dictionaries or favorite repetitive books. You could also partner read and have the child read the nouns, for instance. What a great way to learn grammar, too! But, make it fun; not a chore.

Phonics

Here’s the main benefit of phonics: That children understand sounds create words. That’s it. Let me explain my point. For young left-brained readers, who are part-to-whole learners, it makes a lot of sense to discover that c-a-t makes cat. They get excited. But quickly they convert that knowledge into sight word reading. Each time they come to cat, they don’t sound out c-a-t for long. We all understand that would be a slow and tedious process. You might find with young right-brained readers (between 5 and 7 years old), they continue to sound out c-a-t each time over months. That’s because they are whole-to-part learners and the part-to-whole understanding that sounds make words doesn’t make reading click for them. Not only is it not using their strength, it’s not honoring their learning time frame for reading acquisition (usually between 8 and 10). The reason lies in their pictorial, three-dimensional gift.

The argument that we need phonics to figure out new words is true and false. We  don’t use individual sounds to figure out new words. We tend to chunk words into syllable sound bites. So, to figure out the word contentious, we would see con-ten-tious. That’s a mixture of phonics and sight word/sounds. Fluent readers take only small parts of a word to see the whole. This comes through in the interesting exercise of reading this:

don’t use individual sounds to figure out new words. We tend to chunk words into syllable sound bites. So, to figure out the word contentious, we would see con-ten-tious. That’s a mixture of phonics and sight word/sounds. Fluent readers take only small parts of a word to see the whole. This comes through in the interesting exercise of reading this:

I cnduo’t bvleiee taht I culod aulaclty uesdtannrd waht I was rdnaieg. Unisg the icndeblire pweor of the hmuan mnid, aocdcrnig to rseecrah at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it dseno’t mttaer in waht oderr the lterets in a wrod are, the olny irpoamtnt tihng is taht the frsit and lsat ltteer be in the rhgit pclae. The rset can be a taotl mses and you can sitll raed it whoutit a pboerlm. Tihs is bucseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey ltteer by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe. Aaznmig, huh? Yaeh and I awlyas tghhuot slelinpg was ipmorantt! See if yuor fdreins can raed tihs too.

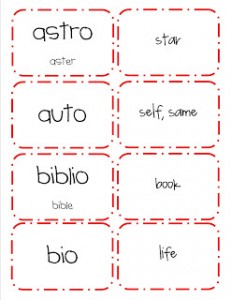

In this same context, some right-brained, whole-to-part learners, may need particular resources to help them notice these chunked parts of a whole. My builder son was like this for spelling. Upon observation, I realized he had no clue how to break a word down. I gave him some resources with Greek and Latin roots after which he excitedly came up to me and declared, “Why didn’t you tell me words were like LEGO!?” His point was that he could see how the individual blocks made the whole creation he made, but he hadn’t seen that words had individual parts that made the whole as well. Most right-brained children will pick this up in the appropriate stage (11 to 13 years old, or 1 to 2 years after reading fluency), but some may have need of being pointed to the right resource to help with the transition.

Intensive Phonics Programs

I’m very careful how I use phonics. My current 12-year-old emerging reader is allowing me to see the reasons more clearly. Starting at 8 to 9 years old, he’s been exposed to the opportunity to learn to read. He’s picked up sight words, and he understands phonics. As the years progressed without fluency occurring, we continued to consistently offer reading opportunities. Periodically, I pick up a new program. One of those programs was ABeCeDarian, a program using the Phono-Graphix method made to be accessible to parents.

There came a time in the program, like most dyslexia programs of this nature, that it is “required” for the child to memorize certain sound combinations. In other words, they want it to be second nature. I instinctively rejected this idea. Why? As I use my honed observation skills with this emerging reader, he shows me he still has an instinct for sight words. Being that he’s a right-brained learner, he often will sound out each word meticulously if pressed to figure it out. If I do this too often, he will begin to continually sound out each word meticulously, thus, joining the ranks of slow, laborious dyslexic readers who, as the Eides have  pointed out, have created their own strange style of reading. Though my 12-year-old falls into the later-than-normal fluent readers, I still have confidence that it will happen for him. I take in all factors, such as his birth father (public schooled) learning to read at 13-14 years old, his high energy level and main outdoor interests, his interest in books more slowly established (yet his reading level increasing as his interest naturally increases), his developmental stages being one stage later than average (so 11-13 years would be his norm), his instinct with reading fluency, and his overall intelligence intact.

pointed out, have created their own strange style of reading. Though my 12-year-old falls into the later-than-normal fluent readers, I still have confidence that it will happen for him. I take in all factors, such as his birth father (public schooled) learning to read at 13-14 years old, his high energy level and main outdoor interests, his interest in books more slowly established (yet his reading level increasing as his interest naturally increases), his developmental stages being one stage later than average (so 11-13 years would be his norm), his instinct with reading fluency, and his overall intelligence intact.

I feel intensive phonics training is potentially more harmful than helpful. It’s a tough call for me to make since it’s accepted that the majority of children are forced to learn to read between the ages of 5 and 7. It appears that even 3 and 4 year olds are being exposed to it as well. Thus, no one considers researching different learning time frames or methods based on learning style. Yet, I feel strongly that those who suddenly come to reading between 8 and 10 after phonics teaching are simply right-brained learners who would have done so anyway if their process had been understood and honored. And those who don’t may have done better with a well-matched learning resource and/or giving them more time. Thousands of stories of later readers should prompt more research in this area to better understand and honor different ways and times for learning.

I end with a philosophical quote from Frank Smith, author of Reading without Nonsense, “a teacher’s responsibility isn’t to instruct children in reading but to make it possible for them to learn to read.” There is a difference! I was fortunate that instinct led me to give space to each of my children to be able to show me how and when they needed to learn to read. I learned a ton through observing their process. It was also highly reinforcing to discover in translation how so much of their process aligns with brain research and learning style differences.

I end with a philosophical quote from Frank Smith, author of Reading without Nonsense, “a teacher’s responsibility isn’t to instruct children in reading but to make it possible for them to learn to read.” There is a difference! I was fortunate that instinct led me to give space to each of my children to be able to show me how and when they needed to learn to read. I learned a ton through observing their process. It was also highly reinforcing to discover in translation how so much of their process aligns with brain research and learning style differences.

What are your experiences or insights regarding learning to read with sight words or phonics?

If you benefited from this content, please consider supporting me by buying access to all of my premium content for a one-time fee of $15 found here. This will even include a 50% off e-mail link toward a copy of my popular The Right Side of Normal e-book (regularly $11.95)!

Pingback: High Frequency and Sight Words Grades K-6 | The Education Cafe

Pingback: An Introduction to the Creative Right-Brained Learner | The Right Side of Normal

Pingback: Learning to Read with Sight Words | The Right Side of Normal