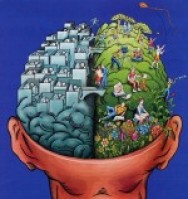

As I researched learning styles, I discovered there were two distinct categories based on brain processing preferences historically referred to as being right-brained (creative) or left-brained (logical). After sharing my knowledge, I was often asked how a person could tell which one best described themselves or their child. As I was writing my book about the subject, I asked myself if there were universal gifts or traits that you could definitely find in each. My answer was yes.

For a person who has left-brained processing preferences, the two universal gifts you will find in them are a word-based (symbolic) focus and a propensity for being able to perform sequential tasks effectively. For instance, as a left-brained processor myself, when I think of the word dog, I might look at my dog, think of the word dog, but I can’t visually see a picture of a dog in my mind. Reading, a word-based and symbolic skill, was something that came naturally and easily to me at an early age (wanting to learn desperately between kindergarten and first grade). I can easily organize things, from checking off to-do lists to putting sentences into a paragraph perfectly supporting each other, to a sheet full of math facts.

For a person who has right-brained processing preferences, the two universal gifts you will find in them are a picture-based (three-dimensional) focus and a propensity for having extraordinary imaginations. For instance, in my right-brained children, if I ask them to think of the word dog, they will visually see a picture of a dog in their mind. They don’t usually see the word for it, just the three-dimensional image of it. Subjects like history and science fascinate these children at a young age because it incorporates picture imagery as a way to best learn the story and the processes found in each. Although most children use their imaginations, you will notice some children, creative children, often go beyond normal childhood play and become their imaginings.

Where do I fit in?

When science chose to reject the labeling called “left-brained” and “right-brained,” recognizing that skills and traits don’t fall neatly into how the brain actually functions, professionals have tried to come up with other descriptors. Linda Kreger-Silverman, for instance, came up with the label auditory-sequential to describe the left-brained learner and visual-spatial to describe the right-brained learner. The only problem with this is that these are not universal gifts. The labels auditory and visual refer to how a person prefers to input  information through a sense. It’s true that processing auditorially does seem to come more commonly easier for left-brained people, but I have several right-brained children who also process information auditorially quite well. And, again, although many right-brained, creative types like to process information visually (because they are pictorial), as a left-brained person myself, I enjoy a good image as well. As for the spatial skill pinpointed for the right-brained person, it does tend to fall in the right-brained spectrum of traits, but I found not all right-brained people were proficient at spatial abilities. Builder types come by them in spades, but artists may be more capable in the visual arena than the spatial. Thus, using Silverman’s categorizations may cause more confusion than clarity.

information through a sense. It’s true that processing auditorially does seem to come more commonly easier for left-brained people, but I have several right-brained children who also process information auditorially quite well. And, again, although many right-brained, creative types like to process information visually (because they are pictorial), as a left-brained person myself, I enjoy a good image as well. As for the spatial skill pinpointed for the right-brained person, it does tend to fall in the right-brained spectrum of traits, but I found not all right-brained people were proficient at spatial abilities. Builder types come by them in spades, but artists may be more capable in the visual arena than the spatial. Thus, using Silverman’s categorizations may cause more confusion than clarity.

If people want to reject the historical categorization of left-brained and right-brained learners, then it is from the universal gifts that a new label would want to  emerge. So, for instance, one could choose the label word-based learners for left-brained people and picture-based learners for right-brained people. Or, to borrow from Silverman’s labeling using a two-part description, a left-brained person could be word-sequential and a right-brained person could be picture-creative (preferring creative over imaginative as it hints at the stereotype for right-brained people as being creative-types). On the other hand, these more precise descriptors tend to end the discussion; whereas, reinventing how the left-brained and right-brained labels are perceived (not literally, but descriptively) simply begins the discussion and the other common traits found in each can be elaborated on as we do on this site and in my book, The Right Side of Normal.

emerge. So, for instance, one could choose the label word-based learners for left-brained people and picture-based learners for right-brained people. Or, to borrow from Silverman’s labeling using a two-part description, a left-brained person could be word-sequential and a right-brained person could be picture-creative (preferring creative over imaginative as it hints at the stereotype for right-brained people as being creative-types). On the other hand, these more precise descriptors tend to end the discussion; whereas, reinventing how the left-brained and right-brained labels are perceived (not literally, but descriptively) simply begins the discussion and the other common traits found in each can be elaborated on as we do on this site and in my book, The Right Side of Normal.

How do I learn?

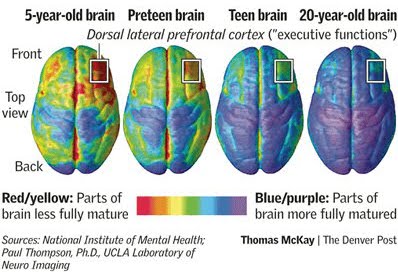

The universal gifts of left- and right-brained people is a crucial piece of information in understanding how the scopes and sequences found in schools should be adjusted to accommodate both brain processing preferences, especially in the early years. This information has a direct correlation in how the brain develops over time and integrates skills and knowledge.

Can we all agree that a baby has a very different brain output than an adult? Not capacity, output. Every baby brain has the capacity to grow into a fully functioning adult brain. It takes time, growth, and maturity. And there are specific stages of growth a brain goes through to reach maturity, or full capacity, as I explain in my most popular post, The Natural Learning Development for Right-Brained Children.

Baby brains begin with sensory input from its environment, to communication input in the ones, to emotional input in the twos, to social input in the threes, etc. I’m not categorizing this literally, because it’s all being integrated at this 0-5 year span. Young babies sift out relevant sounds (Chinese babies keep different sounds in their repertoire than English babies, for instance), learn to communicate (speaking being one of the skills), manage their feelings (terrible twos), develop social reciprocity (community). At 5 (which can often be seen as early as 3), the learning brain begins to show itself more. The brain begins with its natural strength preferences: the traits found in the universal gifts.

From 5 to 7, children engage in activities and skill-building that center in their preferred universal gifts. Left-brained children will be eager to begin to read, write, spell, and understand math facts. If you look at each of these skills, each centers in a word-based focus and sequencing. Right-brained children will be eager to begin to understand history (the stories), science (the real world like animals and dinosaurs), geography (the cultures and myths), and the creative outlets (music, art, building, etc.). If you look at each of these skills, each centers in a picture-based focus and imagination. Doesn’t it make sense that a young brain starts with its strength area?

Currently, schools cater to the universal gifts of left-brained learners from 5 to 7. That is spot on for them. It’s way off for right-brained learners who have a different set of preferred early subject strengths based on their universal gifts.  History, science, animals, cultures, and creative outlets are right up their alley. From about ages 8 to 10, both left- and right-brained learners will start to dabble in their opposite brain processing subject areas. Right-brained children will learn to read and do math facts and left-brained children will incorporate history and science. That said, each learner will still prefer to interact with these subjects using their strengths. Right-brained readers will translate words into pictures, for instance. And left-brained historians will memorize dates and facts. By 11 to 13, left- and right-brained learners will integrate all subjects and skills of both sides, yet still utilizing their universal gifts as the center of how they process information. Thus, knowledge of the universal gifts of left- and right-brained learners is highly important for best educational practices.

History, science, animals, cultures, and creative outlets are right up their alley. From about ages 8 to 10, both left- and right-brained learners will start to dabble in their opposite brain processing subject areas. Right-brained children will learn to read and do math facts and left-brained children will incorporate history and science. That said, each learner will still prefer to interact with these subjects using their strengths. Right-brained readers will translate words into pictures, for instance. And left-brained historians will memorize dates and facts. By 11 to 13, left- and right-brained learners will integrate all subjects and skills of both sides, yet still utilizing their universal gifts as the center of how they process information. Thus, knowledge of the universal gifts of left- and right-brained learners is highly important for best educational practices.

What about my future?

Because the universal gifts are so central and core to our strengths and natural gifts, our future careers often stem from early subject strengths associated with each. For instance, my artist son who began drawing at 3 and loved ancient histories at 5 continues as an artist and a Japanese history buff as an adult. My  writer daughter who wrote short animal stories at 7 continues as a fantasy writer as an adult. My builder son who loved inventing new creations at 4 and playing with pentominoes at 6 is a computer science major and math minor as an adult. I didn’t discover the connection to their adult pursuits with their universal gift development period of 5 to 7 years old until I put together a presentation with a chart of their learning focuses. It was enlightening! How often do we hear the idea that if an adult is in a mid-life crisis or a rut, they are told to think about what they loved as a child and start there in finding a new passion in life?

writer daughter who wrote short animal stories at 7 continues as a fantasy writer as an adult. My builder son who loved inventing new creations at 4 and playing with pentominoes at 6 is a computer science major and math minor as an adult. I didn’t discover the connection to their adult pursuits with their universal gift development period of 5 to 7 years old until I put together a presentation with a chart of their learning focuses. It was enlightening! How often do we hear the idea that if an adult is in a mid-life crisis or a rut, they are told to think about what they loved as a child and start there in finding a new passion in life?

Common left-brained careers might include accountants, non-fiction writers, editors, or lawyers. Common right-brained careers might include interior designer, actor, graphic designer, or fiction writer. Then there are those careers that often have both, each zeroing in on what their strengths bring to the table,  such as marketer, doctor, computer programmer, or scientist. I mentioned this plurality in my book, The Right Side of Normal. I’ve always liked to do different stitching activities. Where my strength lies, however, is in being able to create anything from a pattern. It’s hard for me to create something from my own head because I don’t have visualization skills like my right-brained stitching friends. These right-brained stitching friends often lament their difficulty with patterns. So, a brain preference favoring certain activities or careers doesn’t eliminate that choice; it simply changes the strengths brought to it.

such as marketer, doctor, computer programmer, or scientist. I mentioned this plurality in my book, The Right Side of Normal. I’ve always liked to do different stitching activities. Where my strength lies, however, is in being able to create anything from a pattern. It’s hard for me to create something from my own head because I don’t have visualization skills like my right-brained stitching friends. These right-brained stitching friends often lament their difficulty with patterns. So, a brain preference favoring certain activities or careers doesn’t eliminate that choice; it simply changes the strengths brought to it.

The universal gifts for a left-brained learner and a right-brained learner can help people understand their brain processing preferences. This information should certainly be better incorporated into how we develop learning environments that will enhance the strengths of each type of learner. And it should come as no surprise that many of us will discover that the careers we have pursued, or desired to pursue, can be directly linked to our universal gifts and our interests in our very earliest learning years.

Pingback: An Introduction to the Creative Right-Brained Learner | The Right Side of Normal

Pingback: The Natural Learning Development for Right-Brained Children | The Right Side of Normal

Pingback: Am I Right-Brained Dominant? | The Right Side of Normal