One of my hopeful goals I had for my children’s learning lives is that they would all learn to love reading. Of myself and my three siblings, I was the only one that appeared to love books. My mother’s love of books didn’t seem to transfer to anyone else. As I pondered why, I felt that school destroyed that possibility for my other siblings because of how print materials are used in that environment. Not only does school ruin any pleasure reading by either having to make a book report about it or dissect it into lessons, it also uses poorly written, boring textbooks to cram irrelevant information in their minds strictly in order to sort and categorize them into smart or dumb. Not to mention the negative impact the learning-to-read-too-early process is on many children, particularly boys. They feel these effects pretty young and, often, it steers them away from books completely.

Some of the books from my childhood.

As I pursued this goal of loving to read with my children, I discovered that there was a two-fold strategy that helped me to achieve this. First, I learned to recognize and value the different types of readers (pleasure, information, and instructional). Second, I learned that it was about their relationship with print that mattered, not the actual activity of reading. It’s about how print (books) can lead to exciting and interesting discoveries and adventures. That means books needed to be utilized in a completely different way than schools taught us to use them.

Because I chose to homeschool my children, I could control how books (print) were introduced, interacted with, and valued by my children. I could let the natural unfolding of interacting with books be at the forefront. My children would have to teach me what that looked like by my being an observer and facilitator versus an active participant. The different learning stages meant different interactions and uses of the print resource. This isn’t about reading acquisition (I’ll post about that in a separate article), it’s about how print was a useful and joyful part of my children’s learning lives. Here are some examples from my children for each stage of learning:

During the 5-7 year learning stage, my artist son was into whales. He had a particular book that compared the sizes of whales to a bus. My son decided to make an itty bitty ruler to that scale used in the book, and he would meticulously measure out the length of each whale and hand-draw one to that scale. He spent weeks if not several months doing this. I couldn’t have come up with an assignment near to the learning experience his own inventiveness created!

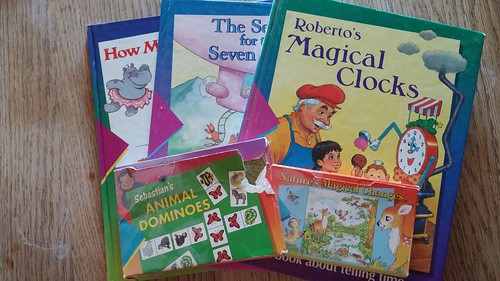

Many of my children enjoyed learning from these “educational books” with a related game on early childhood learning topics during the 5-7 year learning stage.

During the 8-10 year learning stage, my writer daughter was into pleasure reading. I had read aloud the American Girl books to her and her brother, and they became her favorite books thereafter. Without exaggeration, during this learning stage, my daughter read each of these books at least 100 times. At first, I was concerned that she just re-read books of her liking over and over again (there were others besides this particular series as well) and wondered if I should intervene and encourage new readings. She also seemed ready to read more “challenging material,” and again, I wondered if I should encourage her to do so. I decided that I would trust her process. It wasn’t until the 14-16 year learning stage that my daughter took off in her writing endeavors by writing fantasy novels. And at what level of writing did she choose to focus? The level she had spent years reading and re-reading. Was that her natural mentored “learning curve” in being saturated with those who wrote at the level she would eventually write?

Many of my children learned about famous people with this series during the 8-10 year learning stage. Each child would go through a reading and re-reading period with them. I wonder if re-reading is a natural learning method from books?

During the 11-13 year learning stage, my electronics son, diagnosed with autism, who didn’t become a fluent speaker until between 5 and 6 years old, increased his natural interest in books. Although he learned to read between 7 and 8 years old, it wasn’t until the 11-13 year stage that he sought out reading for pleasure a fair amount of time. June B. Jones was his favorite series and it was her humor that he related most to and adopted for himself with his own flair. He often remarks, “Many people with autism don’t know how to have humor, do they? But, I have good humor, don’t I?” Yes, he does!

My electronics son also expanded his book repertoire to include research-based material, which for him, was collecting books about cars that were often related to the timeline of cars and how they changed over the years. He had one such book hat was about 500 pages in length with thousands of pictures of the various American makes and models from their beginning until the year 2000. He wanted to share his interest with the youth at church, so we set up a contest to see if his peers could find a picture of a randomly called make, model, and year on the internet faster than he could find it in this huge volume. He beat the internet every time because of his extensive knowledge learned from this book. This resource also inspired him to make his own timelines on the computer using images found on the internet. He would spend hours and, ultimately, several years doing this.

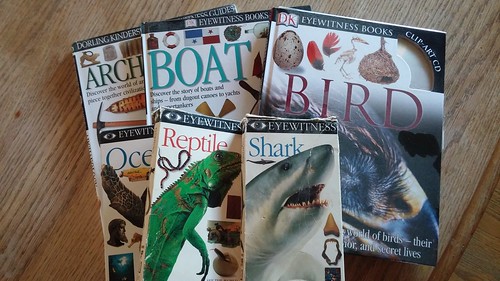

These books and videos were the core science “curriculum” for my oldest son up through the 11-13 year learning stage. All of my children enjoyed these visual books.

During the 14-16 year learning stage, I decided to help my writer daughter learn about and enjoy history more since she didn’t really attach herself to this topic over the years. I knew she liked books and I knew she liked writing, so I found a unit study series that I thought was well-produced surrounding the various topics in world or US history. I introduced the idea to these unit studies, suggested she read the books recommended, and then choose 2-3 activities from the unit study book (versus following the unit study “curriculum” as produced in the book). (In this way, we avoided the “dissection of the book” and simply found a few activities to enhance her understanding of the history involved.)

She agreed to give it a try though she was skeptical since history was not her interest or naturally preferred subject. Several weeks later, she proclaimed to me, “I love history!” A few weeks later, I saw her perfectionism had kicked in and she was “enjoying it so much” that she wanted to do all of the activities, spending hours a day using this resource. On the other hand, she was not meeting her goals with writing her novels, her passion at the time, so I coached her in scaling back on the history unit studies to the 2-3 activities and releasing her need to do it all (all or nothing thinking)(and, yes, I was telling my daughter to do less!). She fell into an appropriate balance between her passion and other studies.

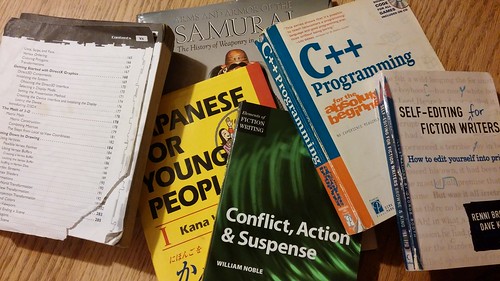

At the 14-16 learning stage, a variety of individualized book resources pertaining to each child’s gifts became prevalent. Actually, throughout all the learning stages each child had a segment of books pertaining to their related interests.

During the 17-19 year learning stage, my builder son, attending community college now, was still trying to figure out how to increase his vocabulary knowledge. He is also diagnosed with autism, and though math and science came easily to him, English and writing did not. We had tried various resources and strategies during the 14-16 year learning stage, traditional ideas like vocabulary lists, mneumonics, and workbooks, but nothing stuck (as most plug and go or memorization activities result). Finally, as I pondered the situation, it occurred to me that it might be a matter of simply exposing him to more vocabulary through natural means. You speak where you are in understanding and exposure was my thinking. For instance, because he had intensely studied computer programming since 13 years old, he had an extensive specialized vocabulary. He just didn’t do things like read for pleasure; he was mostly an instructional reader.

I found the resource, Total Language Plus, that uses books or novels on the market and created vocabulary-based exercises associated with the words found in the reading. I thought simply having him increase his exposure to higher level vocabulary through reading might be useful. Because he had a relevant goal for using this resource in this way, the exercises were part of what helped him versus simply serving to dissect the reading material. Collaborating together for meaningful experiences directly related to my son’s goals for himself makes a huge difference, and as he pursued this strategy of his own volition, he felt it helped him overall.

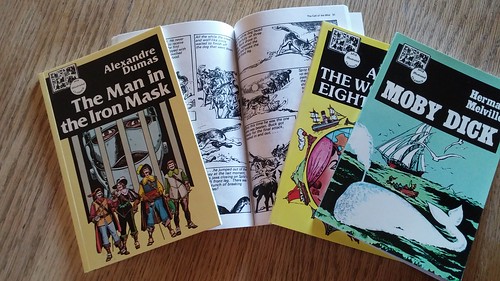

My builder son read all of these visual classics during the 17-19 year learning stage because he was interested in knowing what the classics were about but didn’t want to commit to that level of reading.

Notice that my examples during the 5-7 year and 8-10 year learning stages arose from the natural responses that can occur from natural resources. Going to the library consistently, reading aloud consistently, having books in our home and a bookshelf in each of their rooms, and modeling how books are useful in my own life contributed to a love of learning and a positive relationship to print. The 11-13 year learning stage is a tricky one because I believe you shouldn’t “assign” anything that you don’t want to risk having them hate. So, reading is one of those things I rarely “assigned.” So, it wasn’t until the 14-16 and 17-19 year learning stages that any formal resources were brought in surrounding reading. But, each was relevant and associated with something that would be a help in a weaker area by bringing in something that was positive or a strength: books!

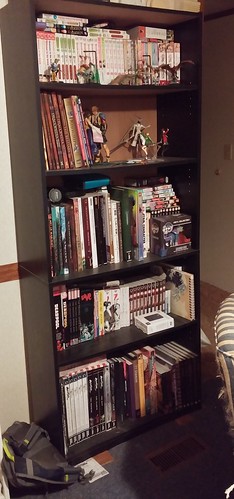

One of three bookshelves at my single adult son’s home.

I’m pleased to say that I met my goal that each of my seven children have a positive relationship with print (this would be rare to find in a family of schooled children). Six of these are boys! I remember a person I hired came to help me work with my fifth son, 15 at the time, with an intellectual disability caused by memory deficits. This means he has difficulty learning to read past the Dick and Jane level because he can’t retain the information. She was aware of this. To the hired person’s surprise, when my son came up from his room to meet her, he told her he had been looking at books. He wanted to continue with her and she discovered he had a stack of books he had been perusing, mostly about Native Americans, his favorite topic. She had been surprised because, most often, if a student attends school and can’t read by his age, there is an obvious avoidance of books. Again, it’s not about reading. It’s about a positive relationship with print in which you can still gain much learning!

I challenge you to allow books to be the teachers as a natural extension of reading them. We don’t have to turn things into lessons. You don’t have to assign reading. Have lots of types of books around the home: pleasure reading books, informational (visual) books, and instructional (how to) books. Value each type of book interaction. Have bookshelves in each child’s room. Go to the library. The learning emerges on its own through the creative and innovative imaginations of each individual person as they seek out their own experiences and knowledge from what matters to them. You, too, can have children with positive relationships toward print!