Writing strikes fear into many homeschoolers trying to figure out the right way to teach it. And there are curriculum producers trying to create the best way to teach the formula. What is writing for, anyway? Maybe that’s where we should begin. For me, great writing inspires action. Sure, I seek out informational writing to learn things. It still holds my attention best with writing that pulls me in. Thus, I believe good writing is substance over style, or in writing terms, voice over formula. How do we accomplish that?

With my children, I learned through them the actual natural progression to writing for those children who come to it in that way. I also learned that there are pre-writing stages such as oral storytelling. And there are different paths to writing based on brain dominance differences. And what about my children who didn’t come to writing naturally? How do they get there? I created my theory based on an unschooling mother and son I listened to at a Growing Without Schooling conference long ago. There was a panel of parent/child and a question was posed on how writing was learned. One mother explained her strategy that worked for them. She would sit next to her son and help him write word for word, if necessary, in the beginning. Eventually, he got the hang of it himself and initiated continuing on his own. It felt shocking to hear. Yet, her words echoed in my mind years later, “How does someone learn to write if not from someone who knows how to write?”

It seems that there is either a hands-off approach to writing because anything else is considered cheating, or there is outright cheating by having a friend or family member actually do the writing for the person. For my children who were not natural writers, I knew there would be little to no progress if we were to rely on traditional teaching methods by giving an assignment, having him work through it himself, and then correct him after the fact. In that format, all sorts of bad habits are formed, you have to fail before you succeed, and it feels like a struggle as you invent the wheel yourself. Pulling the idea from that unschooling parent from years prior, I utilized a way to come to writing I call the mentoring path.

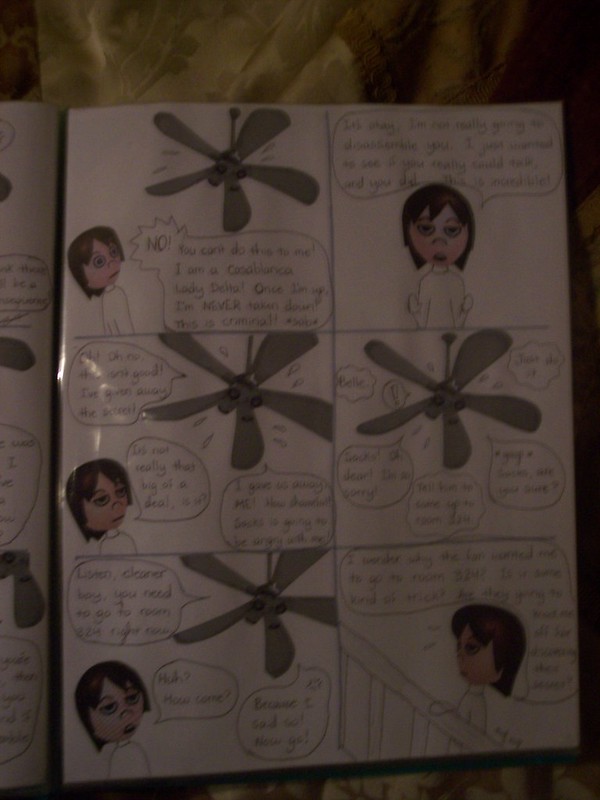

My builder son, diagnosed with high functioning autism, struggled with expressing himself verbally in any form in his early years, including up until the 11-13 year timeframe. And yet, because of our strength-based environment, he did find outlets to express his ideas, particularly through building with LEGO, LEGO Studio, and comic book making, inspired by his oldest brother and his interest in trains. My builder son would create whole words from his building materials; that was his stories. LEGO Studio allowed him to create stop-gap motion movies and bring his LEGO stories alive in a whole new way.

As his brain naturally shifted in that 11-13 year timeframe, he became more aware of his place in the world, and wanted to improve in his weak areas, including English related areas. We started finding ways to improve his spelling and vocabulary, both extreme weaknesses for him. His spelling improved from atrocious to fair, and eventually even to good! Vocabulary was one of those areas tough to improve in but we tried various ideas to slight success. We also developed grammar more, which became a strength because of the sameness of that subject, as well as patterns of knowledge associated with it. In other words, we started with the parts initially, to build a foundation. But, to be clear, these focuses were only about 3-4 times a week for maybe up to 30 minutes. It didn’t become a spotlight; it just showed up on our radar.

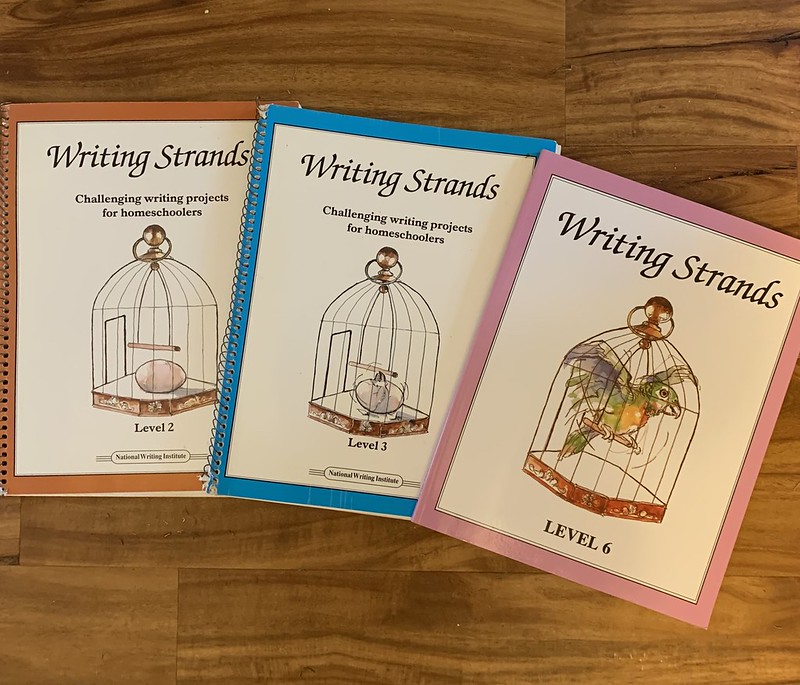

At the 14-16 year timeframe, my builder son was ready to tackle writing. I had him work through some of the Writing Strands books, starting with the Level 2. He wanted a way to start from the extreme basic level of constructing a thought or idea or sentence. The original Writing Strands is voice focused and was made to be student-driven. He worked through these for 1-2 years, I think. Definitely not more than that, and probably more toward the one year mark. He did feel it gave him a basic understanding and proficiency on how to have a basic foundational understanding of sentence structuring. His going through all the Daily Grams which practices sentence combining may have also been a good modeling tool for him. He did the grammar series from the first level as well until the end, which probably took him 3-4 years, starting at around the 11-13 timeframe.

Since my builder son continued to be serious about his desire to attend college, and because of his total lack of writing in any genre form, I decided it would be advantageous for him to work from a more formal text. I wanted to start small and build up. He had no experience with the “read the material and answer the question” format yet, so we started there. Because he is a math/computer/science person, I decided to choose a subject in that genre that he had some interest in and would use in college: science. So, starting at 14, he began working through the Apologia science series, one text per year. I had his father sit with him initially to help him know how to navigate creating answers in verbal sentence formatting. It didn’t take long for him to pick up on how to do that. However, I still had his father check over his work consistently to keep him on the right track in this skill development.

Since that was going well, and he really was quite self sufficient in the short answer verbal response, I decided to give him the opportunity to upgrade his verbal response level, as well as delving in a less strength-based subject, at the latter end of the 14-16 year range. I had him read the chapters to Story of the World because it used more simple language and to-the-point writing which I wanted because it was a weak area for him. My builder son would provide a summary (formally called narration) as a way to help him develop interpreting receptive language into expressive language (in other words, it required understanding what he read and then turning that into written words of explanation of his own). That was a hit and miss endeavor because of inconsistency with availability of his father’s mentorship.

At the 16-17 year range, I decided it might be a good suggestion for him to simply be more exposed to good writing through reading, since he didn’t choose to do that much reading for himself, except for computer texts and manuals. He agreed. So, I invested in some Total Language Plus booklets and encouraged him to read some classics that stretched his understanding level. For him, that was middle school level reading. Because this program was more language intensive in the activities, I felt it might be a good way to integrate spelling and vocabulary and such. It did stretch him and it did seem to give him some overall good exposure and experience with the written word.

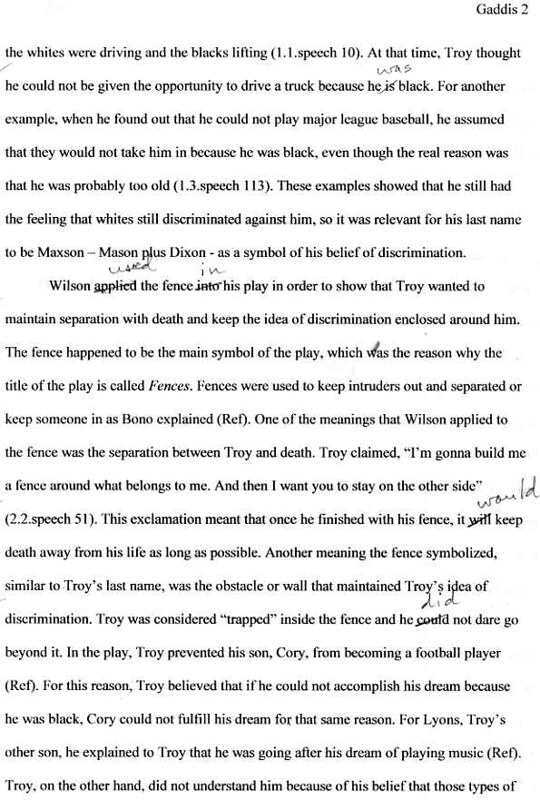

So, between the Total Language Plus activities and readings for exposure, and continuing with the science texts year to year with his father mentoring in that area, as well as periodic summaries in history, my builder son was building a foundation in the manipulation of the English language in all its facets. At 17, he chose to start attending community college to earn his Associates in Science degree. He started off with his strengths first: math. The second semester, he chose to try his first writing course. What we discovered there was it was a better fit for him with English-related topics to choose an on-line course versus an in-class course. In this way, he could always take whatever time he needed to put into the assignment in order to feel comfortable with it. With an in-class course, they often would do some “free writes” in the classroom, and my builder son does not process quickly and his writing would look less developed in those circumstances. Thus, the teacher questioned the discrepancy of his at-home assignments and his in-class ones. We were able to transfer to another instructor who was more understanding of why this occurred, and because her class only met once per week, all the assignments were at-home, with class time devoted to teaching new concepts and working on current papers.

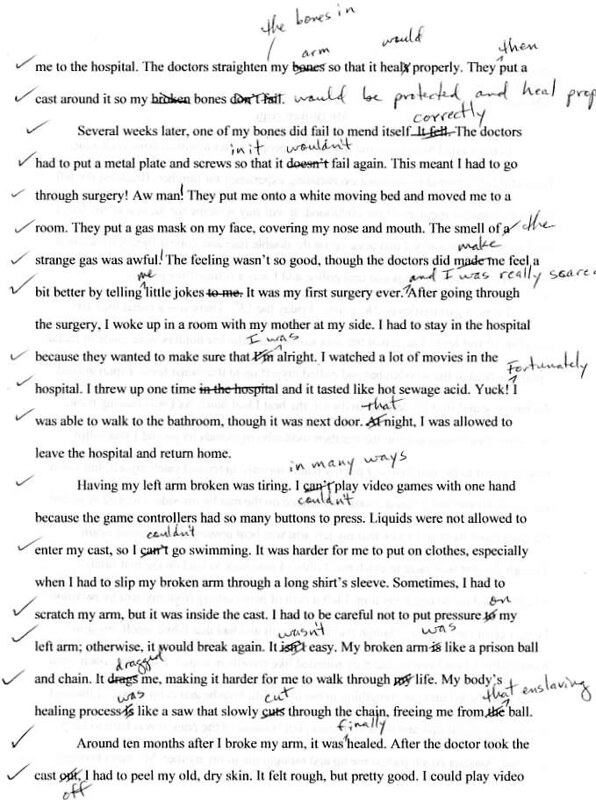

For his assignments, he used his father and I as people who could critique his work in a way that would most benefit him. He wanted any grammar corrections to be edit marked so that he could study his grammar mistake patterns so that he could more effectively correct it. Many were “autism related” as he wrote as he sometimes “spoke autistically”, so it helped him catch those idiosyncracies without being embarrassed. Further, we helped him learn “paragraph patterns” by taking what his teacher was sharing and creating a form initially. Because of these supports individualized in a way that worked best for him, my builder son very quickly was able to become independent in his own edits and putting together effective papers. It was amazing to visually see the number of edits in the beginning of the semester versus the handful or less of grammar edits needed by the end of the semester as well as the quality of writing increase which reinforces the idea of the effectiveness of this type of mentorship.

It all began with the science texts. My husband would help my builder son word for word, if necessary. He quickly understood the pattern of short answers in sentence format, so my builder son only needed periodic advice. For the mentoring with narration summaries, there was more suggestions and specific ideas needed as my builder son learned to organize thoughts and put those thoughts into a cohesive sentence. While reading books that stretched his comprehension, my builder son occasionally would ask his father to help interpret sections with him. Finally, with his college papers, we helped with idea starters, with thought order, and then editing for grammar and flow. That first semester writing class, my builder son might need 3-4 drafts in the beginning, but as shown above, by the end of the second semester class, he was doing most of the things we initially helped him with independently and quite competently. In this instance, it showed that getting rid of our conditioned ideas on teaching writing paved the way for effective mentoring in writing.

Which sets the stage for my next son who developed his writing through mentorship. Growing up, my electronics son always loved to listen to his brother and sister do “cat stories”. These are stories that revolve around our cats that we have, each having their own unique voice and personality. (In fact, my writer daughter made him a three-part video story for Christmas.) In fact, every year for at least three years, she made him stories for Christmas gifts. Subsequently, my electronics son constantly begged his writer sister to do cat stories for him and consistently bothered his artist brother for comic stories.

Since my electronics son was very persistent and didn’t lose interests easily, it was soon apparent that my writer daughter and artist son needed to mentor him in creating these story for his own benefit. My artist son started first and worked alongside my electronics son and taught him to do his own video game playing, which is one venue he liked to have his siblings “make up stories” that correlated with the action involved. After my electronics son learned to play video games, my artist son then helped him create his own commentary as he played. This happened when my electronics son was 10-11 years old.

Around 13 years old, my writer daughter took over and decided to start mentoring my electronics son in story telling. They started out with creating sentences from vocabulary words he was working on. She then expanded him in creating short stories with the list of vocabulary words. When my electronics son was around 14 years old, my writer daughter decided he was ready to learn to write his own stories. It started very much like it was for my builder son and his father, but definitely more help needed. My writer daughter would sit side-by-side with her brother and help him every inch of the way in developing his story, knowing how to proceed and what to write, and how to bring out the personalities of his characters. My electronics son really started to get excited about the idea that he was learning how to create his own stories from his own fingers (through typing).

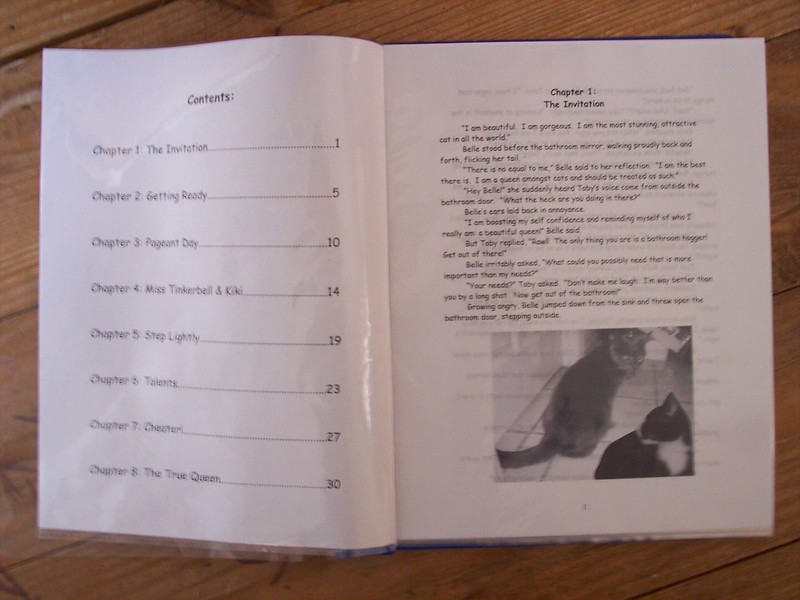

Mentoring had to take a break when my writer daughter went off to college when her electronics brother was 14.5-15.5 years old, but when she returned, they were back at mentoring in writing again. At 16, my electrnoics son begged every day to work on his book. He completed his first story, they edited it together, and he continued to have new ideas for other books. My electronics son reached the stage where my writer daughters simply had to encourage him to write on his own to develop his confidence in his own ability, and it went well. My writer daughter’s eventual husband also mentored my electronics son with his writing as well, so with two different styles of support, it stretched my son even more in writing independently.

It’s interesting to realize after writing this that my two oldest children, who had natural knacks with language and/or writing, when given the time and space to come to that place on their own time table for their own purposes, fell in love with writing. In fact, my writer daughter has been quoted to say, “Writing is like breathing; if I don’t do it, I’ll die.” My next two children, who didn’t have a knack for writing or language, under competent mentorship in the style that they desired to learn for their own purposes, grew to love writing themselves. I remember walking with my builder son on the college campus as we were straightening out some of his classes on writing at the time, he turned to me and said, “Now I understand why my sister loves to write; I’m really enjoying it!” It supports my idea that if a parent (or educator) focuses on creating a positive relationship for each child in each “subject area”, then when it comes time to develop the skills required for adulthood, that child will embrace the process without a negative connotation from previous failed experiences and can even end up liking it versus tolerating it. Pretty cool stuff!

If you would like to read more on this topic, or if you benefited from this content, please consider supporting me by buying access to all of my premium content for a one-time fee of $15 found here. This will even include a 50% off e-mail link toward a copy of my popular The Right Side of Normal e-book (regularly $11.95)!

Pingback: Cheating or Modeling? |

Pingback: Strengths-Based vs. Weakness-Based Education |